In 1528, a Spanish ship landed in or near Boca Ciega Bay and encountered the Tocobaga. Scantily clad and covered in ceremonial tattoos, the Tocobaga were better adapted to the challenging Florida environment than the Spanish, but less than 200 years later, the Tocobaga had ceased to exist as distinct peoples. The path leading to the Tocobaga began as the Ice Age waned. As the planet warmed, the environment changed along with the lifestyles of the people living on the newly formed peninsula. For more than 11,000 years, these first peoples adapted to this changing environment until the early 18th century demise of the Tocobaga marked the end of indigenous settlement on Pinellas Peninsula. Remembering this story is vital in the telling of Pinellas history.

The Ice Age Melts

By about 9500 BCE, the Ice Age was nearing its conclusion, and glacier melt had produced conditions allowing people to fan out across the Americas, including into present-day Florida. This region bore little resemblance to today’s state. Cooler, drier, wider, and covered with hardwood forests, it provided the perfect environment for the proliferation of the very large mammals that typified this era, including mastodons, giant bison, wooly mammoths, and saber-tooth tigers. Newly arrived Paleo-Indians lived in small kin-based groups and used flint-tipped spears to hunt large mammals for food while also trying to stay within range of the relatively scarce freshwater springs. Warming temperatures made it possible for Paleo-Indians to migrate into the region. That same warming, along with prolific overhunting, also brought an end to their way of life. By about 8000 BCE, the Ice Age ended, as did the environment supporting both the hunters and the hunted. Over the next several thousand years, melting waters and rising sea levels reconfigured both land mass and the environment as a new version of Florida emerged.

A New Coastline Brings Change: Tampa Bay & Pinellas Peninsula

A new coastline formed as rising waters narrowed Florida by about 200 miles. Both Tampa Bay and what we now know as Pinellas Peninsula emerged from this reconfiguration of land and sea. The environment changed as well, as the warmer and more humid conditions produced new flora and fauna. The large animals and hardwood forests of the Ice Age gave way to smaller species that thrived in the new freshwater ponds, salt marshes, and estuaries. By about 6500 BCE, the effect of these environmental changes was clear. Florida’s human inhabitants were still primarily hunters, but their nomadic territories became smaller and more regular. This shift, plus the abundance of fresh water, lent itself to an increase in gathering. In particular, Pinellas’s indigenous peoples began to rely more and more on oysters and shellfish as food. In time, that practice rendered them even less nomadic. Over the course of more than 2,000 years, the Pinellas Peninsula significantly changed as a succession of indigenous cultures emerged, overtook, and then gave way to the next. Finally, in the 10th century the most sophisticated (to that point) of these, the Weedon Island culture, began to give way to the influence of the mound-building Mississippians, who had been influenced by both the Aztecs and the Mayans. Archeologists define this latter period on the Pinellas coast as the Safety Harbor culture, but historians use the term Tocobaga, which refers to the group’s tribal name as well as their principal chief and village.

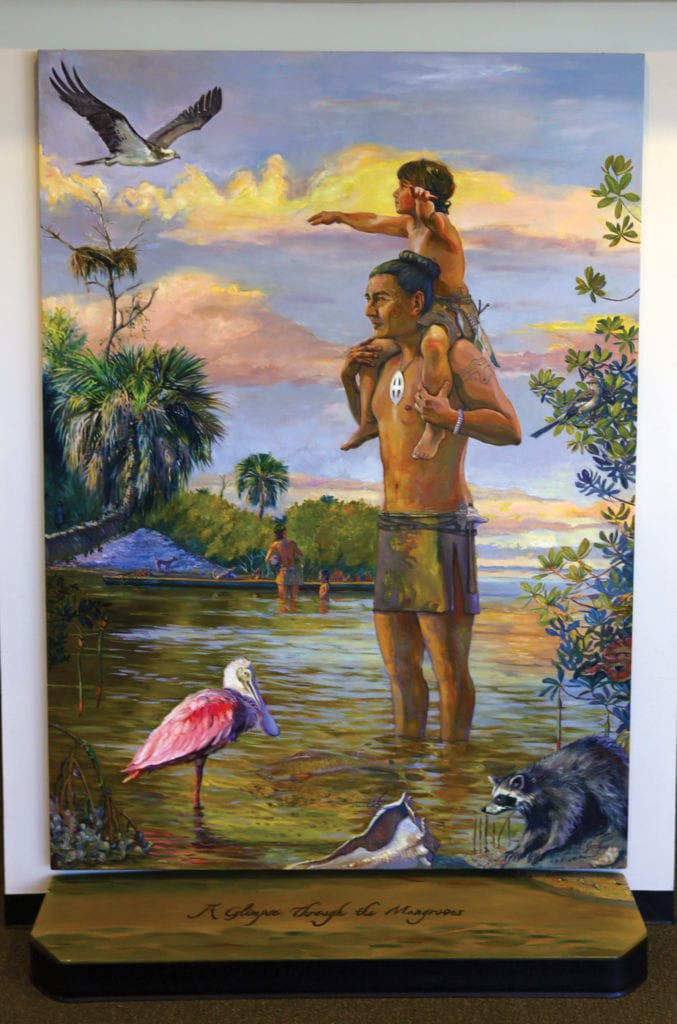

The Tocobaga

Like other mound-building cultures, the Tocobaga society was typified by complex social structures and long-distance trade networks. By the end of the 15th century, the Tocobaga’s coastal domain included from 20,000 to 30,000 people living in dozens of large towns and small villages from present-day Charlotte Harbor to Crystal Bay with the town of Tocobaga (at present-day Safety Harbor) serving as the political and religious center. Each of these towns had its own temple mound, ceremonial plaza, and subchief. As a whole, they formed a loose confederation with varying degrees of loyalty to their chief. Evidence of their increasingly sophisticated culture can be seen in the effort they spent creating ornate ceramics and beautifully crafted jewelry as well as the time spent constructing temples and mounds as part of their elaborate religious life. Maintaining an ecological balance between life and death, or birth and renewal, was paramount to surviving in the challenging environment of Pinellas Peninsula, so these religious and community rituals (structured around the cyclical nature of that lived environment) operated to reinforce balance while also reducing the temptations of territorial warfare. As the 16th century dawned, all evidence pointed to the continued success of the Tocobaga, but the arrival of Europeans on the Gulf coast in the early days of the 16th century upended that balance.

Europeans Bring Change: An End of an Era

The Tocobaga’s extensive trade networks made them well aware of these new peoples and their aggressively violent history years before they met face-to-face. Most present-day historians agree that the first direct encounter between the Tocobaga and the Spanish occurred in 1528 when Pánfilo de Narváez arrived. Over the next 70-plus years, fierce indigenous resistance combined with the effects of the harsh environment eventually convinced the Spanish to give up their fight to conquer and Christianize Pinellas Peninsula. Unfortunately for the Tocobaga, despite the Spanish withdrawal, the die already had been cast. The Spaniards had left behind new plants, animals, and diseases that proved catastrophic to the Tocobaga. Their ecological balance upended and their population ravaged by disease, the last of the Tocobaga were destroyed by a British raiding party in 1709, ending an era begun more than 11,000 years before.

This piece relied on the prior research done by Raymond Arsenault and Jerald T. Milanich.