The sun shines nearly every day and everywhere you look, construction is underway. Tourists fill the downtown streets and newcomers make St. Pete their home in record numbers. As downtown development expands, African Americans increasingly are priced out of their homes and neighborhoods. A new ferry system offers visitors and locals an alternative avenue off and on the peninsula, but complaints about ever-increasing automobile traffic feed demands for better solutions. Soaring real estate prices, an extravagant new pier, and the fate of local baseball are the talk of the town. Sounds familiar, but we’re not talking about today. We’re looking back to the 1920’s and St. Pete’s first big boom.

“A Virtual Paradise”

As a whole, the 1920’s were a time of great contrasts. Nationally, business-friendly policies helped some people get really rich while others struggled to contend with rapidly rising prices and consumerism. Isolationism and anti-immigration sentiments were on the rise. Jim Crow laws, discriminatory policies, and the KKK envisioned an all-white America. Prohibition turned millions into willing cocktail imbibing law-breakers and flappers challenged gender-specific rules of behavior while conservative-minded people decried what they saw as a breakdown of values. St. Pete was not immune to the same issues that plagued other Southern cities, especially in terms of race relations, but that didn’t stop the Sunshine City from marketing itself as a virtual paradise and respite from the real world. The result was rapid growth of population, tourism, construction, and land speculation.

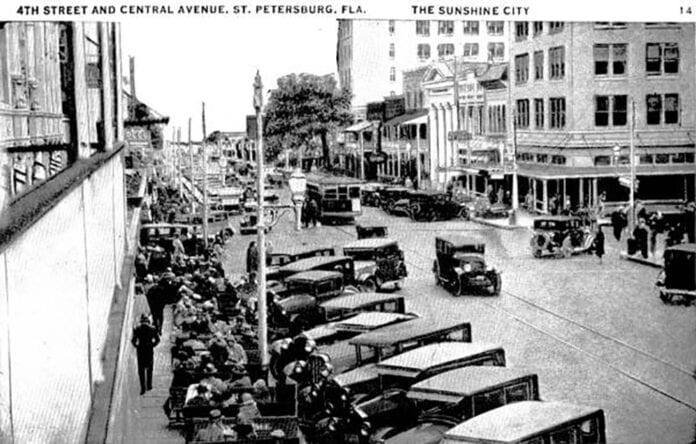

Expansion

Between 1920 and 1930, St. Pete’s full-time population tripled from 14,000 people to over 40,000 and tourism reached new heights. That’s a lot of new people to move around! By the early 1920s, St. Pete jumped on board the 20th century automobile transportation revolution, spending millions of dollars to pave, construct, and extend roadways and bridges. Even more exciting (and transformative) was the bridging of the Bay in 1924. Two years after The Gandy Bridge opened, the Bee Line Ferry debuted, offering direct links from DTSP to northern Manatee County for people AND their cars. As transportation shifts made it easier to get to and navigate within St. Pete, a housing boom looked to accommodate the nearly twelve new residents arriving every day. Between 1920 and 1924 the number of building permits issued skyrocketed from $3 million to $24 million in construction value. At the peak, nearly 50 subdivisions and 6,000 real estate agents competed for dollars and buyers. Many of these planned communities never came to fruition but (thanks in part to dredging and landfilling) by 1926, the city borders had expanded from eleven to fifty-four square miles. Several of St. Pete’s bestknown surviving neighborhoods trace their beginnings to this time, including Allendale, Snell Isle, and Euclid.

Building Up

Despite the flood of new locals, tourism remained the lifeblood of the city and St. Pete used a wide variety of tactics to lure visitors. A weekly “Tourist News” magazine boosted the city. Publicity stunts, such as the “Purity League” bathing suit inspectors, reminded northerners about the beauty of both beaches and sunbathers. In 1920, the marketing strategy proved so successful that hundreds of room-less visitors camped out of their cars at a makeshift “Tent City.” It was clear: the city needed more rooms—lots of them!

Developers quickly complied. Between 1921 and 1928, St. Pete added at least eleven new hotels, including two still in use (Vinoy Park and Don Ce-Sar) and several that have been repurposed (Princess Martha, Jungle Country Club, and the Rolyat). These hotels added thousands of rooms as well as hundreds of jobs but, like most venues (and neighborhoods) in St. Pete, they were strictly segregated. In reality, African Americans made up nearly 20% of the city’s population but marketing materials (and Jim Crow laws) envisioned a “white” city, so black residents could work as hotel maids or bellhops but were banned (along with black tourists) from renting rooms or enjoying the entertainment amenities.

Time to Play

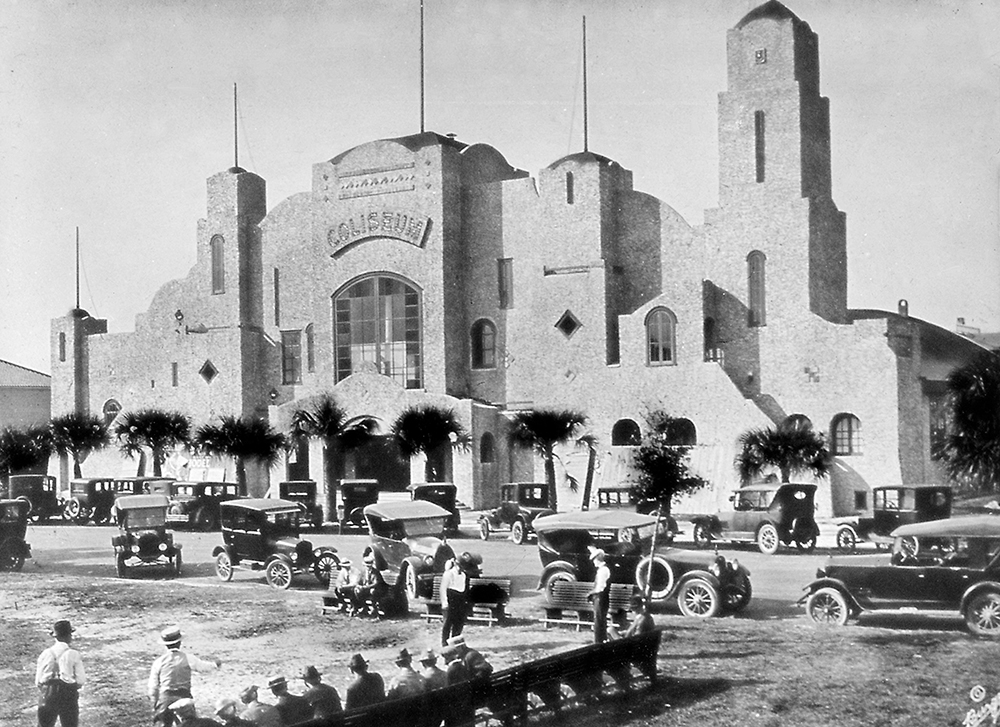

Fun in the sun was the centerpiece of St. Pete’s marketing strategy (as was the lax enforcement of Prohibition) but the beach life was only a small part of that fun. New entertainment venues sprung up all over town. The 1400-foot “Million Dollar Pier” proved to be the most popular attraction. Its 1925 opening provided visitors a solarium, a bathhouse, and a two-story building with a central atrium, open air ballroom, and an observation deck—all accessible by car or trolley. But that wasn’t all the 1920’s offered. Tourists (and locals) could shuffle at the Shuffleboard Club (1923), visit the history museum (1922), bet on a greyhound race (1925), shoot a round of golf at one of the four newly-built courses, or watch Babe Ruth and the newly arrived (1925) Yankees play during spring training. In 1924, the Coliseum (“St. Petersburg’s Palace of Pleasure”) provided a brand-new dance hall and the Florida Theatre (1926) provided an air-conditioned spot to see a show. Like area hotels, most entertainment venues banned black patrons, but the 1924 inauguration of the 22nd St. South Manhattan Casino provided African Americans a welcoming spot for dancing and performances by a wide variety of legendary black entertainers.

The Crash Comes Early to St. Pete

All things (good and bad) eventually come to an end or at least take a turn. For St. Pete, that turn came in 1927 when the land speculation pyramid collapsed. Check back next issue for that story!

Sources available on request but include the prior research of Raymond Arsenault, Will Michaels, Jon Wilson, and Rosalie Peck.