By the 1890s, St. Petersburg was a bustling community of nearly 1,600 people, and although the sun and the sea offered opportunities for sport and relaxation, people increasingly looked inland for new entertainment choices.

“Keep on the Sunny Side”

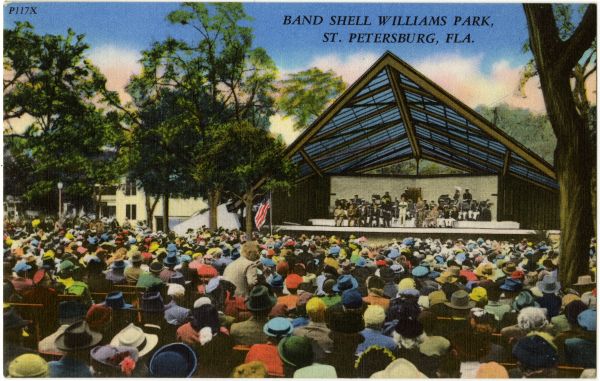

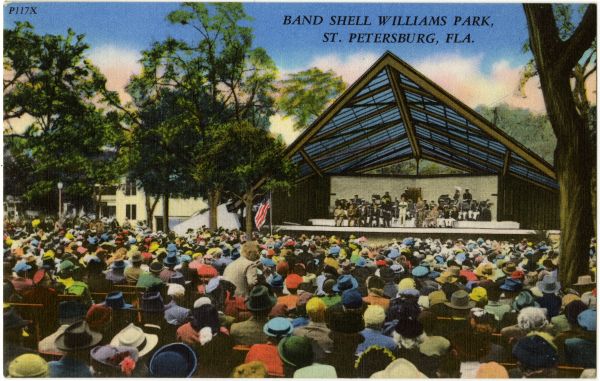

By 1895, City Park (later renamed Williams Park, for city cofounder John Constantine Williams Sr.) served that role. Its newly tamed green spaces along with walkways, benches, and a bandstand provided the perfect venue where white locals and tourists could stroll, listen to weekly concerts or speakers, play horseshoes (or chess, checkers, and dominoes), and enjoy the beautiful weather. The 20th century’s growing population gave rise to a desire for “higher” culture. Armistead’s Opera House answered that call. Considered the social center of town, it drew patrons who donned their most elegant attire (purchased, perhaps, from J.C. Williams’ fine-goods store) to enjoy the opera’s many productions. Of course, not everyone sought higher culture. Mixing a bit of Florida kitsch with the excitement of new technology provided another option: William “Alligator Man” Carpenter’s Royal Palm Theater. Carpenter opened the town’s first “moving picture” house in 1905. He also kept a caged alligator in front of the adjoining gift shop, where for 10 years he sold live alligators and other curiosities.

“Hail, Hail, the Gang’s All Here”

By 1915, the Royal Palm (which would close in 1916) faced serious competition. Silent films had become the No. 1 entertainment choice, and theaters like the Star, Grand, and Rex responded with abundant options. As the St. Petersburg Times noted, in the week before Christmas 1915, patrons could choose from a wide variety of “high-class photoplays,” including Mary Pickford’s Madame Butterfly at the Star Theater and the four-part film The Reward at the Rex, “graphically portraying a girl’s struggle against poverty and the Easiest Way.” As popular as movies were, live entertainment still attracted patrons. For them, La Plaza Theatre may have been St. Petersburg’s most exciting addition. Built in 1913, with a seating capacity of 1,800 people (in a town of only 7,000), the Mediterranean Revival-style building was dubbed “(George) Gandy’s White Elephant” until its success erased doubts. Opening with the Royal Italian Company’s Il Trovatore, it continued to offer a wide variety of live performances until converting to a movie theater in the 1920s. Not all of its offerings were such “high” culture, however; only two weeks after its grand opening, La Plaza featured the Honey Boy Minstrels (a troupe comprised of “sixty corkers,” a slang term for “blackface”), which were “guaranteed to entertain any man alive and his wife and his daughters and his sisters and brothers.” A timely reminder that even though La Plaza was the only theater in town that allowed Black patrons, albeit segregated in the balcony, Jim Crow-style racism was firmly established by the beginning of the Great War.

“Ain’t We Got Fun?”

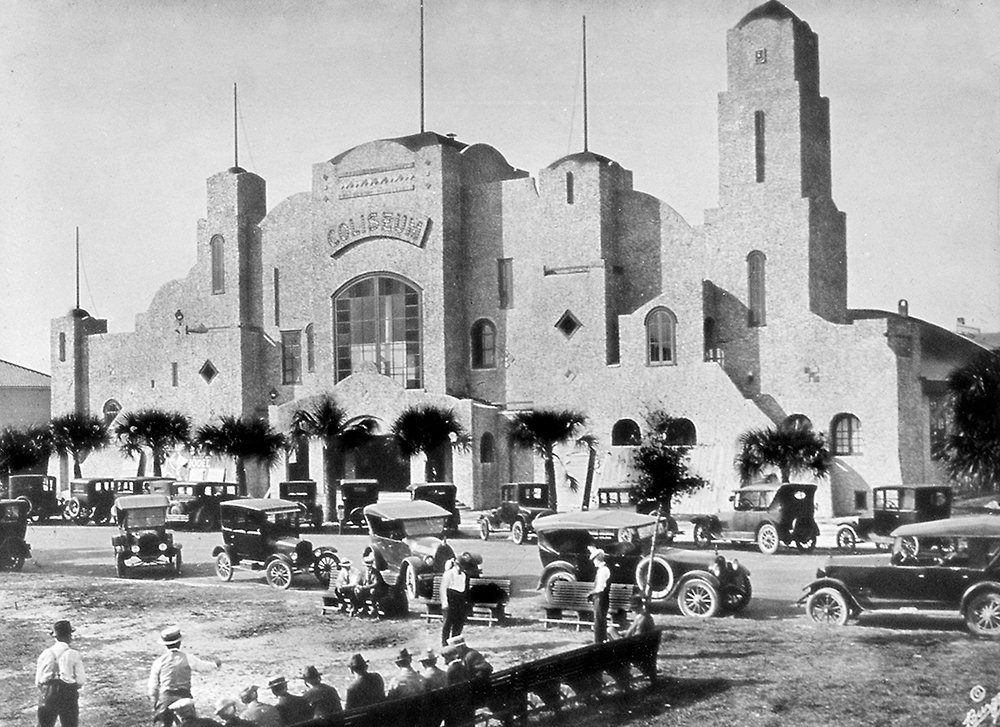

World War I and a global pandemic overshadowed much merriment, but by 1920, happy days were here again! The roar of the 1920s brought a dizzying array of entertainment options, and the newly built Florida Theatre may have been the best ticket in town. Described as a “Castle in Spain come true!” it featured 2,300 seats, 2,000 lights, nine dressing rooms, and the “exuberant flamboyance” of imported Spanish art. Plus it was air-conditioned, a first for St. Pete! But for some, sitting in a theater (even a cool one) just didn’t fit their recipe for fun. They wanted to move. And places like the open-air ballroom at the new Million Dollar Pier and the extravagant Coliseum answered that call. Receiving rave reviews as St. Petersburg’s “Premier Play Palace,” the Coliseum offered an 1,800-square-foot dance floor and seating capacity for more than 4,000 patrons. Hosting popular touring bands led by Benny Goodman, Guy Lombardo, and Cab Calloway, the Coliseum was a hit. Like most other venues in town, its “whites only” policy for patrons was strictly enforced. In response to this pervasive segregation, Elder Jordan opened the Manhattan Casino (originally called Jordan Hall) in 1925. Serving as a cultural and social center for the African American community, this dance hall attracted an astounding level of talent during its heyday, including B.B. King, Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles, Duke Ellington, and Little Richard.

For some, the 1920s also signaled a growing “flirtation with decadence,” as one historian described it. Thanks to lax local enforcement, Prohibition didn’t stop revelers from adding liquor to their pursuit of pleasure. Local bootleggers made sure that the dance halls and local nightclubs like the Gangplank in the Jungle area and Spanish Bob’s on the Snell Arcade rooftop were well-supplied. As the 1920s roared, it looked as if the fun would never stop.

“Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off”

The Great Depression that began in 1929 and World War II did lower that roar. The midcentury advent of television and home air-conditioning units changed the entertainment landscape, as did expanding suburbanization and decreasing segregation. One by one, once-popular spots went dark. By the end of the 1960s, even mainstays such La Plaza, the Florida Theatre, and the Manhattan Casino had shut their doors. In the 50 years since, St. Petersburg has boomed, gone bust, and boomed again. Throughout that half-century, a myriad of spots fought for entertainment dollars as one thing remained constant: St. Pete liked to have fun!