Many of us watched the news of garbage strikes in Paris this past spring with something akin to horror. Inconvenience and unsightliness aside, can you imagine the stench that piles of uncollected trash would create if such a strike happened in sweltering Florida? During the summer of 1968, St. Petersburg residents didn’t have to imagine it. They lived it.

It happened just a month after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. during a sanitation workers strike in Memphis, Tenn. Neither strike took place in a vacuum, erupting during one of the most tumultuous years in American history, one rocked with Vietnam war protests, civil rights activism, and enormous social flux.

On its face, St. Petersburg’s sanitation strike was a protest of wages and working conditions, but underlying these factors was the city’s long history of segregation and racism. For decades, the city was governed by official rules and social customs that dictated where and how black citizens could live, attend school, vote, and even where they could swim or sit (not on the green benches, for one). Largely restricted by both law and custom to low-wage jobs, substandard housing, and underfunded schools and medical facilities, African-American citizens nevertheless created a thriving and productive community that made up about 15% of the city’s population.

Origins of the strike

Long-simmering discontent finally came to a head among the city’s sanitation workers, who were almost exclusively African-American. In early 1968, a new garbage route system was implemented, meant to reduce the work-week from six days to five. With fewer hours, crews would make less money, roughly $75 dollars a week compared to the $100 a week they’d made on the old schedule. The sanitation workers, many of whom had been at the job for decades, knew the new schedule was unfeasible; there simply wouldn’t be enough time to pick up all the garbage. Their complaints fell on deaf ears, but workers were told that if they went along with the new system, the city would review its savings after 30 days and pass along some of the money to the workers in the form of a pay raise. The 30-day deadline came and went with no action from the city.

On May 6, 1968, after weeks of delay tactics from the city, workers began what City Manager Lynn Andrews would call a “wildcat strike.” He gave them a day to reconsider their actions, and when they still didn’t show up for work he summarily fired 211 men, all but one of them African-American. He promptly hired new workers, mostly young white men, and paid them higher wages.

It was not the first time Andrews was at odds with the city’s sanitation workers. Hired in 1961, he had presided over two previous strikes in 1964 and 1966, during which he referred to sanitation workers as ignorant and illiterate, accusing them of “goofing off” in order to collect overtime pay. Still, those early strikes resulted in marginal wage increases for workers and the creation of an unofficial union, the Young Men’s Progressive Club, led by sanitation crew chief Joe Savage. When the club was formed in 1964, Savage had been working for the city sanitation department for 17 years. He was a respected member of the community: a deacon and head of the male chorus at his church, and the father of seven children. He became the spokesperson for the striking men, while attorney James Sanderlin represented their interests to the city.

A Long Hot Summer

The 1968 strike stretched on for months, although Andrews refused to acknowledge it as such, stating that the workers had been fired and therefore could not engage in negotiations. Replacement workers were hired, and residents still were asked to haul their own garbage to various collection sites. (Striking workers voted to use their own personal trucks to haul garbage for invalids.) Weeks of nonviolent protests were sporadically marred by the firebombing of strikebreakers’ cars and incidents of arson.

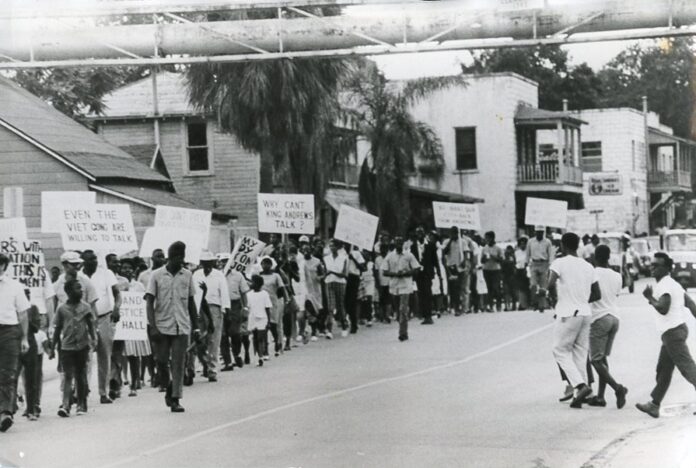

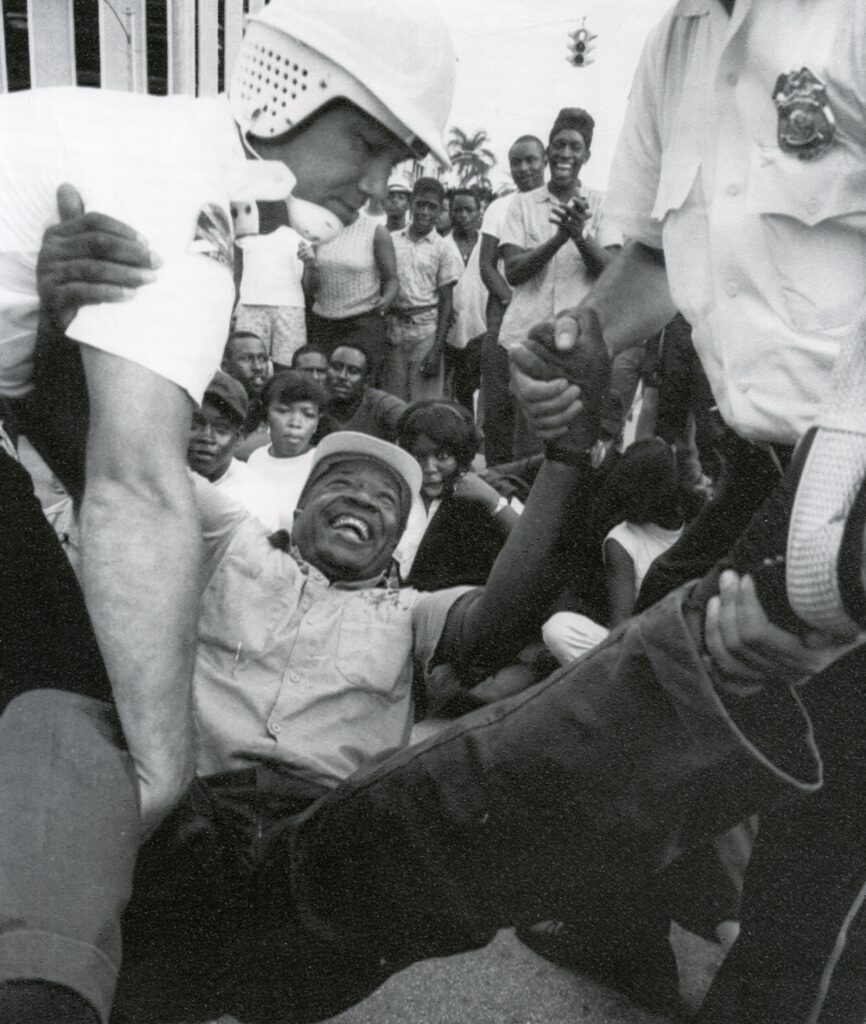

As the strike entered its fourth month it gained national attention when the Rev. A.D. King, brother of slain activist Martin Luther King Jr., and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, came to St. Petersburg to bolster protesters’ spirits. They drew an interracial audience of more than 1,000 people to the Gibbs High School auditorium for rousing speeches. A few days later, on Aug. 3, some 650 marchers strode down Central Avenue, arms linked 20 abreast, to protest at City Hall. It was one of more than 40 protest marches conducted during the strike.

As the summer and the strike dragged on, the heat, and tempers, flared. In mid-August, tensions boiled over into three days of rioting, mostly in historically black neighborhoods. There were dozens of arrests.

Public opinion was decidedly mixed. Most citizens quoted in the St. Petersburg Times seemed to agree that the strikers had a valid complaint: a promised raise that wasn’t delivered. But everyone wanted to see an end to the violence and the long days of stalemate.

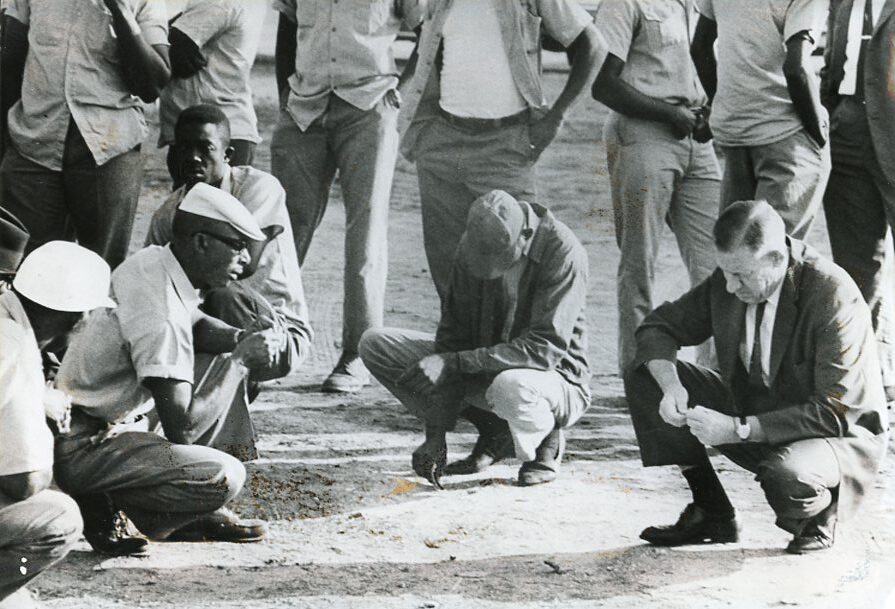

Pressure mounted. Mayor Don Jones broke with Andrews, backing the workers’ claims of undelivered commitments and poor communication from the city. The newspaper ran an editorial titled “End it Now.” Displaced workers suffered after four months on the picket line.

An Uneasy Compromise

By late August, talk of a settlement began to circulate. On Aug. 31, Andrews announced in a press conference that an agreement had been reached. The Times noted that both Sanderlin and Savage were “conspicuously absent” from the announcement. Instead, local accountant David Welch (father of current Mayor Ken Welch) was present as a representative of the recently formed Community Alliance, an arm of the Chamber of Commerce designed to facilitate communication between black and white residents of the city. (The Community Alliance remained a major force in the city for decades afterward.)

The settlement delivered marginal victories to the workers. They would get their jobs back, but only as positions became vacant. They would return to their original six-day work schedule with a slight increase in pay equivalent to what replacement workers received, but they would lose any accrued sick pay, vacation time, and even seniority. The immediate “wins” were hollow, but the long-term benefits proved to be substantial.

The strike proved that the voices of African-American workers in the city carried weight: They had agency. Soon after the strike, and almost certainly as a direct result of it, the city’s first African-American council member, C. Bette Wimbish, was elected. Sanderlin, the sanitation workers’ lawyer, would go on to become Pinellas County’s first black judge. Within two years, the sanitation workers organized their first official union. No longer could they be silently taken advantage of.

A City Moves Forward

Of the two major figureheads in St. Petersburg’s 1968 Sanitation Workers’ Strike, Andrews and Savage, one would remain working for the city until his retirement in 1987 and have a city building named after him. The other would be gone from the city payroll by 1969.

In 2006, the City of St. Petersburg unveiled the new name of its Sanitation Department headquarters: the Joe Savage Complex. (The city named its first African-American Sanitation Department director that same year.) Andrews resigned in 1969, leaving Florida to take a city manager position in Texas. He later returned to St. Petersburg to work in the private sector. In 2003, city residents voted to change from a city manager form of government, to a strong mayor format; never again would an unelected official hold as much power as Andrews once did.

The 1968 Sanitation Workers’ Strike would prove to be one of the most pivotal civil rights actions in St. Petersburg’s history. It forced inequalities into the open, and required ordinary citizens to face the city’s problems in a visceral way. The summer of our discontent helped pave the way for a more equitable St. Petersburg.