In December of 1925, a cold and rainy week cast a rare cloud over the booming Sunshine City, perhaps foreshadowing changing times. In the coming months, the land speculation schemes driving much of that boom collapsed, leaving unfinished projects and rising unemployment in its wake. Still, the sun shone most days and the national economy continued to flourish, so tourism kept the city from falling into a deep economic pit. Then, in October of 1929, the stock market crashed.

The Great Depression Descends on St. Pete

Very quickly St. Pete’s precarious stability was upended and the city dove into a five-year economic descent. Without any viable safety nets, many people suffered – some more than others. Businesses failed and homes were lost. Unemployment skyrocketed and wages nosedived, especially for those dependent on the dwindling tourist market. Panicked depositors lined up outside banks to demand their cash and by April of 1931, every bank in town had closed its doors. The city itself was in deep financial trouble. Financing infrastructure improvements seemed smart in the booming 1920’s, but by 1931, St. Pete had defaulted under the weight of the second highest per capita debt load in the nation. Many businesses as well as governmental entities (including the county schools) were forced to pay their employees in scrip (essentially a paper IOU). Meanwhile, the city council counted on the citizen-led “Home Patronage Committee” to reduce (or eliminate) the influx of potentially needy newcomers. Signs on the edge of town announced, in no uncertain terms, “DO NOT COME HERE SEEKING WORK—A CITY’S FIRST DUTY IS TO EMPLOY ITS OWN CITIZENS.”

A New Deal for Some

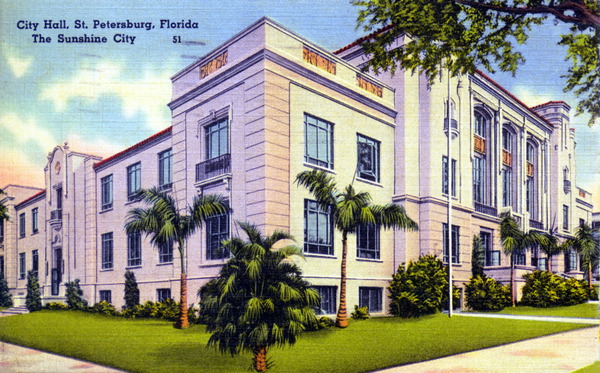

The state of Florida was nearly bankrupt itself. St. Pete looked to the federal government for aid, successfully obtaining one of the few projects meted out by the Hoover administration: a grant to build the Bay Pines VA hospital and office on city-donated land. The construction jobs helped but the crisis was bigger than one project, as a 1932 St. Petersburg Times headline declared “Crippled World Plumbs Its Ills in Search of A Cure.” Simply put, things were bleak, which explains why many traditionally conservative St. Pete voters shifted course as part of 1932’s “ROOSEVELT LANDSLIDE.” After the election, the city continued to lobby hard (and successfully) for New Deal dollars. Between 1933 and 1941, the federal government pumped over 10 million dollars into the city’s economy in the form of relief payments, public works projects, and military expenditures. Among other things, New Deal money helped fund mosquito control, road repairs, the beach water system, a Coast Guard station, the Treasure Island Causeway, a new St. Pete Junior College campus, and a new city hall. Funds also helped support cultural endeavors such as orchestras, art clubs, sewing rooms, and theaters as well as sponsoring projects aimed at indexing historical materials and cataloging public records. Undoubtedly, the New Deal helped some but not everyone benefited equally.

Not Really a New Deal

Local governments had considerable control over how New Deal funds were meted out; in this case, African Americans frequently were underserved or left out of programs completely. St. Pete’s Black community was hardest hit when jobs dried up. Jim Crow segregation laws also continued to limit or deny access to everything from beaches and green benches to libraries and restaurants. Efforts to expand disenfranchisement escalated as St. Pete adopted a “white primary” strategy meant to reduce Black attempts to vote for change. Often forced by racist policies and unscrupulous landlords to live in substandard and overcrowded homes even before the Depression hit, the city further codified segregation during this period. In 1931, and again in 1936, the city council approved resolutions further defining where Black people could live and do business. In addition, local law enforcement as well as the local Ku Klux Klan continued to use violence in their attempts to enforce Jim Crow laws and racist traditions.

Fighting for Change

Despite these challenges, resistance expanded. Beating back fierce opposition from white slumlords, a New Deal housing act helped fund the construction of Jordan Park. This new development did nothing to challenge segregation but it did provide better housing for African Americans during a time when nearly 60% of the Black population had been denied access to electricity, compared to just 2% of the white population. Groups like the NAACP strengthened and individual local Black activists like Reverend John Wesley Carter and Chester Lucas James, Sr. vocally demanded the same things that local whites enjoyed, including decent housing, running water, electricity, paved streets, the right to vote, and access to city services and recreation facilities. As always, Black women, like Fannye A. Ponder, stepped up. Among other efforts, Ponder helped to organize the “City Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs” to unite Black women’s efforts to “promote better educational advantages, to further social and civic improvements … and educate the citizenry towards better and higher standards of living.” Foundations for change were being laid.

The Worst is Over?

By 1935, the shining sun, a slowly improving national economy, and a vigorous public relations campaign brought an upsurge in tourism. As this shift helped lift St. Pete above the worst effects of the Depression, two things seemed clear: the crash laid bare St. Pete’s dependence on tourist dollars while it also further exposed the community’s deep racial divide. These intertwining realities proved critical in shaping the future of the Sunshine City.

Sources available upon request.