In December of 1941, the United States declared war on the Axis Powers and officially entered a war already raging overseas. Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor, policymakers in the United States had anticipated our escalating involvement with a series of actions that brought the overseas war effort closer to Tampa Bay and changed St. Pete’s future path.

The Best Laid Plans

In the year leading up to Pearl Harbor, locals followed the war news, registered for the draft as required by the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 (the first peacetime conscription act in U.S. history), and contributed to the budding defense industry. The 1941 Lend-Lease Act escalated manufacturing meant to supply material aid to the war effort in Europe. Campaigns reminded people that the old family coffee pot could become part of an airplane and urged “housewives … to turn any old pots, pans, and other scrap … over to the government for defense purposes.”

Throughout 1941, however, locals eyes also were on area political issues, including how St. Petersburg chose its mayor and a proposed liquor ordinance that mandated daily closing times and complete closures on all Sundays and election days. To many, war seemed far away. Organizers couldn’t even drum up a robust show of support for a volunteer Home Defense Unit. Meanwhile the Chamber of Commerce budgeted $100,000 to promote tourism “in the warmth of the subtropics” and predicted a record season. The December declaration of war after the surprise of Pearl Harbor changed everything. All eyes turned to the war. Local tourism was initially crippled and the already existing military presence escalated.

The Military Moves In

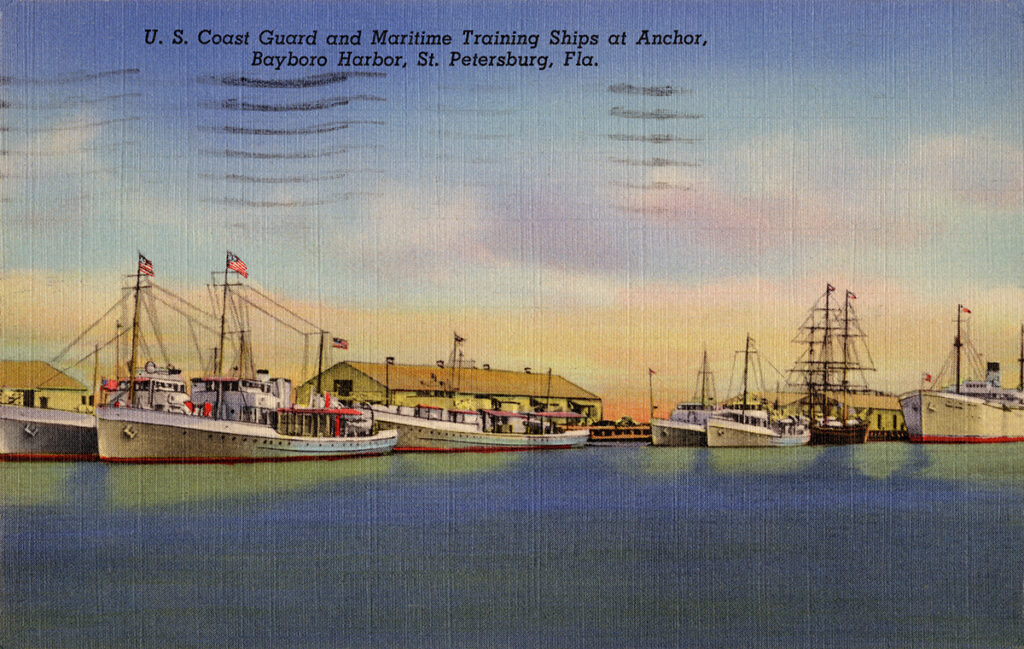

Two years before the United States officially entered the war, the U.S. Coast Guard Air Station at Bayboro Harbor began conducting antisubmarine air patrols over the Gulf of Mexico as a result of the 1939 Presidential Proclamation prohibiting submarines from belligerent nations from entering American ports. That same year the Coast Guard also reopened its Bayboro Harbor naval base as a training station for merchant seamen. By 1940, two training ships were bringing in a steady stream of training recruits as dredging and filling expanded the base and reshaped the shoreline. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, even bigger changes unfolded. Local officials lobbied hard to convince the government that St. Pete was a perfect place to house and train newly drafted and volunteering soldiers. In June 1942, that effort was rewarded as soldiers began to arrive for Army Air Corps technical service training. Over the next year, more than 100,000 trainees filled almost every major hotel and camped out at the Piper Fuller Airport and Jungle Club Golf Course. The Army Air Corps left in July of 1943, but those rooms remained filled as the maritime training facility at Bayboro Harbor expanded and the Army Transport Corps Marine Officers Cadet School arrived. A significant number of pilots also trained at Pinellas Army Air base (north of St. Pete) and at MacDill Field (in Tampa), and those trainees also regularly made their way to the Sunshine City. In addition, many soldiers brought their families to live with them during training. Hotels, streets, bars, beaches, and restaurants were overflowing in a “sea of khaki,” but St. Pete also experienced a boom in house and apartment rentals and purchases as many military families decided to remain in town after soldiers shipped overseas.

“Sure the Army’s Here, But St. Petersburg Can House You Too”

Tourism took a big hit in early 1942, as travel restrictions and gas and oil rationing kept people at home. Many popular seasonal attractions also were canceled for the duration of the war, including the Festival of States, the St. Petersburg-to-Havana yacht races, and spring training baseball games. Nevertheless, the Sunshine City still had warm air and sunny skies, and boosters quickly developed a marketing strategy that took advantage of those assets. Pivoting from the idea of travel as a luxury, they promoted St. Pete’s “winter visitors” as patriots. Visiting or relocating to Florida freed rooms for workers in crowded defense-industry cities and eased the need for heating oil. Campaigns urged northerners to get their “Vitamin V for Victory at Sunny St. Pete” and reminded them they could get their “sunshine quota” in “America’s sunshine base for freedom.” Extensive national ad campaigns, as well as a 5000-mile circuitous booster road trip from Florida to Milwaukee and back, emphasized that, even with the military in town, St. Petersburg still had 60,000 rooms available for rent. Targeting the elderly, those unfit for service or defense work because of their health, and the families of soldiers, the Chamber of Commerce and other boosters spent tens of thousands of dollars to attract people to the city. Their efforts paid off. Promoters estimated their efforts brought $50 million into the local economy.

After the War: St. Pete Booms

At the war’s end, the military mostly left, but the wartime influx of soldiers and their families as well as the “winter visitors” set the stage for a major demographic expansion. Many soldiers either stayed or returned after the war. They were joined by throngs of other people looking to make a fresh start or enjoy the winters in the Florida sun. By 1950, St. Pete’s year-round population was nearing 100,000 people with winter numbers far beyond that. This growth led to a building boom that boosted the local economy in myriad ways. The next few decades presented numerous and serious challenges, especially in regard to the fight for racial equality and environmental protections, but wartime shifts contributed to the foundation for a changed city and a postwar boom in prosperity.

Sources include St. Petersburg & the Florida Dream by Ray Arsenault and Warm Wishes From Sunny St. Pete by Nevin D. Sitler.